2. Beijing United Family Hospital and Clinics, Beijing 100015, China

2. 北京和睦家医院检验科, 北京 100015

-

1 评估方法和依据

- 1.1 标本收集

- 1.2 实验试剂及材料

- 1.3 弯曲菌选择性培养基及增菌液的制备

- 1.3.1 Karmali选择性培养基的制备

- 1.3.2 增菌液的制备

- 1.4 培养及鉴定

- 1.5 荧光定量PCR法

- 1.6 统计学分析

- 2.1 患者一般情况

- 2.2 菌株鉴定

- 2.3 分离培养结果

- 2.4 real-time PCR直接检测结果

- 2.5 2种方法检测腹泻患者粪便标本空肠弯曲菌的阳性率

感染性腹泻是细菌、病毒或寄生虫感染胃肠道 后导致的一种常见症状,是引起世界范围内发病 和死亡的第二大原因[2],发达国家尽管生活水平和教育水平较高,但感染性腹泻仍然是一个重要的公共卫生问题[3],而在发展中国家,急性感染性腹泻是导致1~3岁儿童发病和死亡的主要原因之一[4],是导致儿童营养不良最常见的原因[5]。目前,在欧美等经济发达国家,空肠弯曲菌感染导致的腹泻居于病原菌感染导致腹泻的首位[6],而国内最新报道显示[7],腹泻患者空肠弯曲菌检测的阳性率为7.1%,已经超过志贺菌(5.7%)并有逐渐增加的趋势。除了急性肠胃炎,空肠弯曲菌感染可导致严重的后遗症如格林-巴利综合征,反应性关节炎及肠易激综合征等[8]。

病原菌的分离培养是目前弯曲菌感染临床诊断的金标准[9],目前我国腹泻患者中弯曲菌的感染现状报道较少,可能与空肠弯曲菌的体外培养条件较苛刻以及肠道菌群的耐药从而使弯曲菌选择性分离培养的难度增大有关 [10-11]。实时荧光定量聚合酶链反应(real-time PCR)方法也可以用于腹泻患者粪便中弯曲菌的检测[12],但目前对real-time PCR检测方法的灵敏度报道不一,Sloan等[13]对200份临床粪便标本检测表明以培养分离法为“金标准”比较时,real-time PCR法灵敏度较低,约为70%。而Kulkarni等[10]和Logan等[14]研究表明real-time PCR法和分离培养法检测同一份标本的阳性率并无明显差别。

为获得当前我国感染性腹泻患者弯曲菌感染的现状,本研究通过连续收集北京某医院2013年4 11月278份感染性腹泻门诊病例粪便标本,使用直接划线培养、增菌培养和real-time PCR法直接检测腹泻患者粪便中弯曲菌的感染情况,并比较不同方法检测结果的差异。

持续收集某医院2013年4 11月期间就诊门诊的感染性腹泻患者粪便标本,感染性腹泻标准见参考文献[2],即患者有如下临床表现:大便次数增多(每天3次及以上)、大便性状改变,可表现为水样便、黏液便、血便、稀便、脓血便等,收集标本前使用抗生素者排除,共获得278份新鲜粪便标本。

Karmali培养基(CM0935)、Columbia培养基(CM0331)、2号营养肉汤(CM0067)和弯曲菌选择性添加剂(SR0205E和SR0204E)及弯曲菌生长添加剂(SR0232E)购自OXIDE公司,无菌脱纤维绵羊血(博瑞生物科技有限公司)、微需氧产气袋GENbag Microaer(cat 45532)购自法国生物梅里埃公司,粪便提取试剂盒QIAamp DNA stool Minikit (cat#51504)购自QIAGEN公司,快速革兰染色液购自珠海贝索生物技术有限公司,氧化酶测定试剂盒(REF:55635)和触酶ID-ASE购自(REF:55561)购自法国Biomerieux SA公司,Star Marker(D2000)购自北京康润诚业生物科技有限公司,空肠弯曲菌阳性对照菌株ICDCCJ07001由中国疾病预防控制中心传染病预防控制所诊断室保存。

培养基的配制按照说明书进行,称取21.5 g Karmali干粉溶于500 ml蒸馏水中,充分溶解,121 ℃高压15 min。冷却至50~54 ℃,加1瓶Karmali选择性添加剂(SR0205E),混匀,倾注平皿备用。

2号营养肉汤的制备按照说明书进行,称取12.5 g 干粉溶于500 ml 蒸馏水中,充分混匀,121 ℃高压15 min,冷却至50~54 ℃,分别加1瓶弯曲菌选择性添加剂(SR0204E)及弯曲菌生长添加剂(SR0232E),充分混匀,分装5 ml增菌液至离心管中4 ℃保存备用。

采集标本后立即由在医院专门医生直接划线接种培养基:取黄豆大小新鲜标本直接溶于500 μl~1 ml无菌生理盐水中,混匀,用移液器吸取100 μl混合液直接转移到选择性培养基,分区划线;增菌划线培养:同一份标本同时吸取100 μl粪便标本转移到5 ml增菌液中,立即放入带微需氧产气袋的密闭盒中,4 h内送实验室转移至42 ℃三气培养箱(5% O2,10% CO2 和85% N2)中增菌24 h后,吸取100 μl增菌液转移到选择性培养基上划线培养。接种好的选择培养基均置于42 ℃三气培养箱(5% O2,10% CO2 和85% N2)培养观察2~3 d。挑取可疑菌落进行革兰染色镜检,氧化酶、触酶做初步鉴定,用多重PCR进行弯曲菌的验证及种属分类,具体操作见[15] 。

核酸准备按照QIAamp DNA stool Minikit的说明书进行,探针、引物及具体操作步骤见[9,16] 引物、探针由上海生工生物工程公司合成。

采用Excel 2007 和SPSS 18.0统计软件管理和分析数据,计量资料采用均数±标准差表示(x ±s)。两种方法检测阳性率差异的比较使用 McNemars test检验[17],以P<0.05为差异有统计学意义。

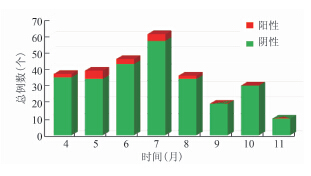

符合感染性腹泻病例定义的278例患者中,使用2种方法检测共有16例空肠弯曲菌阳性标本,患者年龄分布从0~46岁不等,其中0~4岁5例,14~44岁10例,>44岁1例。男性10例,女性6例。4 11月阳性率分别为5.4%(2/37)、12.8%(5/39)、6.5%(3/46)、6.6%(4/61)、5.5%(2/36)、0(0/19)、0(0/30)和0(0/10),5、6和7月检出率高于其他月份,经检验P=0.3958,差异无统计学意义。阳性率在不同月份的分布见图1。

Figure 1 C. jejuni positive samples from diarrheal patients in different months

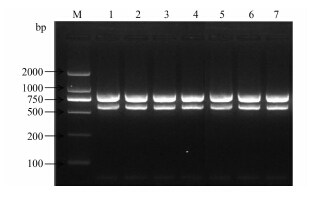

菌株多重PCR鉴定结果见图2,目的条带与预期特异条带长度相一致。部分标本real-time PCR鉴定结果见图3,Ct(Cycle threshold)值<30为阳性标本。

图2 多重PCR鉴定结果

Figure 2 Electrophoresis results of mPCR

图3 部分标本real-time PCR结果

Figure 3 Real-time PCR results for stool samples from diarrheal patients

278份标本中共分离到6株空肠弯曲菌,阳性率为2.2%,其中直接划线分离到6株,增菌培养分离到2株,分离培养结果见表1。

表1 直接划线和增菌划线分离培养结果Table 1 Isolates from direct medium cultured and enrichment culture

| 标本编号 | 直接划线培养 | 增菌培养 |

| 17 | +(C.jejuni) | +(C.jejuni) |

| 54 | +(C.jejuni) | +(C.jejuni) |

| 144 | +(C.jejuni) | - |

| 174 | +(C.jejuni) | - |

| 185 | +(C.jejuni) | - |

| 191 | +(C.jejuni) | - |

278份标本中使用real-time PCR法共检测到14份空肠弯曲菌阳性标本,阳性率为5.0%。其中,10份标本PCR检测阳性但分离培养阴性,检测的平均Ct值为29.15±0.88;2份标本分离培养阳性但real-time PCR检测阴性。

如表2所示,real-time PCR检测腹泻患者粪便中弯曲菌的阳性率14/278(5.0%)高于病原分离培养法6/278(2.2%),经McNemars test检验,2种方法检测粪便标本中弯曲菌的阳性率的差异有统计学意义(χ2=36.425, P=0.039)。直接划线法分离的阳性率2.2%(6/278)高于增菌法0.7%(2/278),2种基于细菌培养方法分离弯曲菌的阳性率的差异有统计学意义(χ2=50.617, P=0.000)。

表2 2种方法对粪便标本中弯曲菌检测的差异Table 2 Difference in detection of C. jejuni between culture-based method and real-time PCR

| 荧光定量PCR法 |

| 合计(份) |

| + | 4 | 10 | 14 |

| - | 2 | 262 | 264 |

| 合计(份) | 6 | 272 | 278 |

弯曲菌是引起急性胃肠炎的常见食源性病原菌[18]。本研究中278份感染性腹泻患者标本使用2种方法共检测出16份空肠弯曲菌阳性标本,分离培养法和real-time PCR法检测的阳性率为分别为2.2%和5.0%。国内曾有报道腹泻患者弯曲菌的分离培养阳性率为0.39%~11.36%[19-23] ,尤其是儿童弯曲菌的感染率为2.30%~11.36%,而PCR检测的阳性率为0~16.9%[9,24] ,国外Buchan等[25]对1244份腹泻患者粪便标本进行弯曲菌分离培养及real-time PCR法检测,得出2种方法检测的阳性率分别为1.8%和2.3%,与本调查结果相似。根据现有的数据,5 7月检出数高于其他月份,但这3个月是否弯曲菌的感染率要高于其他月份,需要长时间进行监测和检测分析。

病原培养法和real-time PCR法均可用于腹泻患者标本中弯曲菌的检测,但2种方法的灵敏度和特异度不同,本次real-time PCR法检测患者粪便标本中弯曲菌的灵敏度(14/16,87.5%)高于分离培养法(6/16,37.5%),Sivadon-Tardy等[26]使用培养法和real-time PCR法同时检测格林-巴利综合征患者粪便标本中的弯曲菌时也发现real-time PCR法敏感性要高于培养法。但文献[27]通过比较不同PCR方法,发现real-time PCR虽然能提高检测的速度,但检测的灵敏性会下降;而分离培养病原菌对病原进一步分析具有重要意义[28,30] ,如对病原菌进行分子分型以对相关暴发事件进行病原溯源和对弯曲菌进行遗传进化研究等。

此次检测中,real-time PCR法检出率(5.0%)显著高于分离培养(2.2%),但分离到的6株弯曲菌均为单菌落,同时这6份分离到菌株的标本real-time PCR检测弯曲菌时Ct值均值高于29(其中包括2份分离培养阳性但real-time PCR检测阴性标本,Ct值分别为31和35),表明患者感染量菌量并不大,这可能是本次分离培养检出率降低的原因。虽然粪便中有PCR抑制物如胆酸、胆红素、血红素或复合碳水化合物等[31,32] ,但此次粪便标本使用Qiagen粪便提取试剂盒提取了高质量的DNA,最大程度去除PCR抑制物的影响,因此本次研究real-time PCR方法的灵敏度高于分离培养。本次实验中部分标本划线后使用微需氧产气袋运送至实验室,而在过程中产气袋中氧气浓度的逐渐下降等不利的生长环境可能会使弯曲菌处于“活的非可培养状态”[33,34] ,但real-time PCR检测不受细菌存活与否的限制,因此也会造成real-time PCR法检测率高于分离培养法。

2种基于病原分离培养的检测方法中,直接划线法弯曲菌分离率2.2%(6/278)高于增菌法0.7% (2/278), 结果与Agulla等[35]的研究结果相似,即增菌并不能明显增加腹泻患者粪便标本中弯曲菌的分离率。但也有研究表明增菌法能显著提高感染菌量较小(<104/g粪便)的腹泻患者粪便标本中弯曲菌的分离率[36]。本研究前期通过模拟实验分别从增菌肉汤和固体培养基中添加不同的弯曲菌选择性添加剂从而增加了杂菌筛除的概率,同时对于增菌液中羊血以及血清的使用也分别通过在弯曲菌阴性的粪便样品中掺入不同浓度的弯曲菌后进行不同培养条件的比对,同样获得模拟粪便标本中弯曲菌的检出率均为直接划线法优于增菌培养法。本次研究结果表明粪便标本的直接划线培养是弯曲菌基于病原分离培养检测方法的首选方法。

总之,本研究使用不同的检测方法获得了北京某医院腹泻患者弯曲菌的感染现况。对于腹泻患者粪便标本中弯曲菌的检测方法,real-time PCR法和培养法各有优缺点,real-time PCR省时省力,不依赖菌株分离结果,适合病原的快速筛检及对病原进行流行病学调查,但培养法简单实用,可以获得致病菌,更适合病原实验室常规监测及进一步分析。2种方法联合对弯曲菌病的检测有很大帮助,对于弯曲菌病的预防和控制有重要的公共卫生意义。

[2] Guerrant RL, Van Gilder T, Steiner TS, et al. Practice guidelines for the management of infectious diarrhea[J]. Clin Infect Dis,2001,32(3):331-351.

[3] Hilmarsdottir I, Baldvinsdottir GE, Harethardottir H, et al. Enteropathogens in acute diarrhea: a general practice-based study in a Nordic country[J]. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis,2012,31(7):1501-1509.

[4] Azemi M, Ismaili-Jaha V, Kolgreci S, et al. Causes of infectious acute diarrhea in infants treated at pediatric clinic[J]. Med Arh,2013,67(1):17-21.

[5] Bonkoungou IJ, Haukka K, Osterblad M, et al. Bacterial and viral etiology of childhood diarrhea in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso[J]. BMC Pediatr,2013,13:36.

[6] Coker AO, Isokpehi RD, Thomas BN, et al. Human campylobacteriosis in developing countries[J]. Emerg Infect Dis,2002,8(3):237-244.

[7] Li Y, Xie X, Xu X, et al. Nontyphoidal Salmonella infection in children with acute gastroenteritis: prevalence, serotypes, and antimicrobial resistance in Shanghai, China[J]. Foodborne Pathog Dis,2013,published online Dec 6, doi:10.1089/fpd.2013.1629.

[8] Mughini GL, Smid JH, Wagenaar JA, et al. Risk factors for campylobacteriosis of chicken, ruminant, and environmental origin: a combined case-control and source attribution analysis[J]. PLoS One,2012,7(8):e42599.

[9] Zhang MJ, Qiao B, Xu XB, et al. Development and application of a real-time polymerase chain reaction method for Campylobacter jejuni detection[J]. World J Gastroenterol,2013,19(20):3090-3095.

[10] Kulkarni SP, Lever S, Logan JM, et al. Detection of Campylobacter species: a comparison of culture and polymerase chain reaction based methods[J]. J Clin Pathol,2002,55(10):749-753.

[11] Wang DG, Bao CM, Chen SM, et al. Distrubution and drug resisitence characteristics of intestinal bacterium in the last 10 years in China[J]. Chinese Journal of Health Laboratory Techology,2010,20(9):2385-2388.(in Chinese) 王大刚,鲍春梅,陈素明,等. 中国近10年肠道菌群分布及耐药特点[J]. 中国卫生检验杂志,2010,20(9):2385-2388.

[12] Maher M, Finnegan C, Collins E, et al. Evaluation of culture methods and a DNA probe-based PCR assay for detection of Campylobacter species in clinical specimens of feces[J]. J Clin Microbiol,2003,41(7):2980-2986.

[13] Sloan LM, Duresko BJ, Gustafson DR, et al. Comparison of real-time PCR for detection of the tcdC gene with four toxin immunoassays and culture in diagnosis of Clostridium difficile infection[J]. J Clin Microbiol,2008,46(6):1996-2001.

[14] Logan JM, Edwards KJ, Saunders NA, et al. Rapid identification of Campylobacter spp. by melting peak analysis of biprobes in real-time PCR[J]. J Clin Microbiol,2001,39(6):2227-2232.

[15] Zhang MJ, Gu YX, Ran L, et al. Multi-PCR identification and virulence genes detection of Campylobacter jejuni isolated from China[J]. Chinese Journal of Epidemiology,2007,28(4):377-380.(in Chinese) 张茂俊,顾一心,冉陆,等.空肠弯曲菌多重聚合酶链反应基因鉴定及其毒力相关基因分析[J]. 中华流行病学杂志,2007,28(4):377-380.

[16] Qiao B, Xu XB, Zhang MJ. Real-time PCR development for identification of Campylobacter coli from stool specimen[J]. Chin J Zoon,2012,28(10):969-972.

[17] Lund M, Nordentoft S, Pedersen K, et al. Detection of Campylobacter spp. in chicken fecal samples by real-time PCR[J]. J Clin Microbiol,2004,42(11):5125-5132.

[18] Allos BM. Campylobacter jejuni Infections: update on emerging issues and trends[J]. Clin Infect Dis,2001,32(8):1201-1206.

[19] Liao HZ, Lin M, Zhou LY, et al. Epidemic status investigation of Campylobacter jejuni in the patients with diarrhea living in Nanning,Guangxi[J]. Journal of Applied Preventive Medicine,2013,19(3):132-134.(in Chinese) 廖和壮,林玫,周凌云,等. 广西南宁市腹泻人群空肠弯曲菌流行状况调查[J]. 应用预防医学,2013,19(3):132-134.

[20] Huang JL, Xu HY, Bao GY, et al. Epidemiological surveillance of Campylobacter jejuni in chicken, dairy cattle and diarrhoea patients[J]. Epidemiol Infect,2009,137(8):1111-1120.

[21] Xu HY, Huang JL, Bao GY, et al. Prevalence and antimicrobial susceptibility of Campylobacter spp.in diarrhea patients in Yangzhou[J]. Chinese Journal of Zoonoses,2008,24(1):58-62.(in Chinese) 许海燕,黄金林,包广宇,等. 扬州市区腹泻人群空肠弯曲菌和结肠弯曲菌流行状况及耐药性分析[J]. 中国人兽共患病学报,2008,24(1):58-62.

[22] Zhou H, Chen SS, Deng QL. The obvious seasonality of Campylobacter jejuni infectious in children[J]. Guangzhou Medical Journal,1998,29(4):46-47.(in Chinese) 周宏,陈树生,邓秋莲. 儿童空肠弯曲菌感染的明显季节性[J]. 广州医药, 1998,29(4):46-47.

[23] Chen ZX, Lyu DS, Wan SP, et al. Epidemiological Investigation of Campylobaeter jejuni Infection in Children[J]. Chinese Journal of Preventive Medicine,1995,29(3):144-146.(in Chinese) 陈志新,吕德生,万绍平,等. 儿童空肠弯曲菌感染的流行病学研究[J]. 中华预防医学杂志,1995,29(3):144-146.

[24] Wang XH, Cai L, Hu TY, et al. Nosocomial diarrhea in intensive care unit: other than Clostridium difficile[J]. Journal of Sichuan University: Medical Science Edition,2013,44(4):637-640.(in Chinese) 王晓辉,蔡琳,胡田雨,等. ICU病房的非艰难梭菌相关性医院感染腹泻[J].四川大学学报:医学版,2013,44(4):637-640.

[25] Buchan BW, Olson WJ, Pezewski M, et al. Clinical Evaluation of a real-time PCR Assay for Identification of Salmonella, Shigella, Campylobacter(Campylobacter jejuni and C.coli), and Shiga Toxin-Producing Escherichia coli Isolates in Stool Specimens[J]. J Clin Microbiol,2013,51(12):4001-4007.

[26] Sivadon-Tardy V, Orlikowski D, Porcher R, et al. Detection of Campylobacter jejuni by culture and real-time PCR in a French cohort of patients with Guillain-Barré syndrome[J]. J Clin Microbiol,2010,48(6):2278-2281.

[27] Hilscher C, Vahrson W,Dittmer DP. Faster quantitative real-time PCR protocols may lose sensitivity and show increased variability[J]. Nucleic Acids Res,2005,33(21):182.

[28] Zhang MJ, Zhang JZ. The drug resistence status of Campylobacter jejuni[J]. Diasease Surveillance,2007,22(12):793-811.(in Chinese) 张茂俊,张建中. 空肠弯曲菌耐药现状[J]. 疾病监测,2007,22(12):793-811.

[29] Olsen SJ, Hansen GR, Bartlett L, et al. An outbreak of Campylobacter jejuni infections associated with food handler contamination: the use of pulsed-field gel electrophoresis[J]. J Infect Dis,2001,183(1):164-167.

[30] Miller WG, Englen MD, Kathariou S, et al. Identification of host-associated alleles by multilocus sequence typing of Campylobacter coli strains from food animals[J]. Microbiology,2006,152(Pt 1):245-255.

[31] Iijima Y, Asako NT, Aihara M, et al. Improvement in the detection rate of diarrhoeagenic bacteria in human stool specimens by a rapid real-time PCR assay[J]. J Med Microbiol,2004,53(Pt 7):617-622.

[32] Lund M,Madsen M. Strategies for the inclusion of an internal amplification control in conventional and real time PCR detection of Campylobacter spp. in chicken fecal samples[J]. Mol Cell Probes,2006,20(2):92-99.

[33] Bessede E, Delcamp A, Sifre E, et al. New methods for detection of Campylobacters in stool samples in comparison to culture[J]. J Clin Microbiol,2011,49(3):941-944.

[34] Silva J, Leite D, Fernandes M, et al. Campylobacterspp. as a Foodborne Pathogen: A Review[J]. Front Microbiol,2011,2:200.

[35] Agulla A, Merino FJ, Villasante PA, et al. Evaluation of four enrichment media for isolation of Campylobacter jejuni[J]. J Clin Microbiol,1987,25(1):174-175.

[36] Hutchinson DN, Bolton FJ. Is enrichment culture necessary for the isolation of Campylobacter jejuni from faeces?[J]. J Clin Pathol,1983,36(12):1350-1352.

|

扩展功能

|

|

| 本文信息 | |

| PDF全文 | |

| HTML全文 | |

| 参考文献 | |

| 服务与反馈 | |

| 加入引用管理器 | |

| 引用本文 | |

| Email Alert | |

| 本文作者相关文章 | |

| 刘夏阳 | |

| 于俊峰 | |

| 顾一心 | |

| 梁昊 | |

| 张茂俊 | |

| PubMed | |

| Article by LIU Xia-yang | |

| Article by YU Jun-feng | |

| Article by GU Yi-xin | |

| Article by LIANG Hao | |

| Article by ZHANG Mao-jun | |